These motions [Note 1] concern the ownership to and rights over an approved subdivision roadway known as Peter's Way in a subdivision in Sudbury. The defendant Sudbury Station, LLC intends to use this road as a means of access to a parcel on which it plans to construct a 250-unit affordable housing development (the "Project") pursuant to G.L. c. 40B. The Town of Sudbury Zoning Board of Appeals (the "board") approved the defendants' application for this development, but with conditions, unacceptable to the developer, that significantly reduced the number of units that could be constructed. Count One of the present amended complaint is an appeal by the plaintiffs pursuant to G.L. c. 40B, § 21 of this approval, and Count Two is a claim for declaratory judgment with respect to the parties' respective legal rights in Peter's Way. In a separate action, Sudbury Station, LLC also appealed the conditions of the Board's approval to the Housing Appeals Committee ("HAC") pursuant to G.L. c. 40B, § 22. On the plaintiffs' motion, this court accordingly stayed Count One, the plaintiffs' G.L. c. 40B, § 21 appeal, pending the outcome of the defendants' HAC appeal. See Taylor v. Bd. of Appeals of Lexington, 451 Mass. 279 , 272, n. 4 (2008) (requiring that the court stay an abutters' appeal of a G.L. c. 40B approval pending resolution of the developer's appeal to the HAC). The court allowed the plaintiffs' motion to amend the complaint to add factual allegations concerning Count Two. The claims addressed on the present motions concern only Count Two, which alleges that the defendants lack the legal right to use Peter's Way for access to the property on which they propose to build the Project. The plaintiffs argue that the fee to Peter's Way passed to plaintiff Erica Andrews by operation of G.L. c. 183, § 58, also known as the "derelict fee statute." In the alternative, the plaintiffs argue that Erica Andrews has acquired an easement by estoppel over Peter's Way. For the reasons stated below, the court finds that the underlying fee in Peter's Way passed to plaintiff Erica Andrews by operation of the derelict fee statute, but that the extent of the defendants' rights of access over Peter's Way, if any, by easement by estoppel, cannot be determined on the current record.

UNDISPUTED FACTS

The following material facts are found in the record for purposes of Mass. R. Civ. P. 56, and are undisputed for the purposes of the motion for summary judgment:

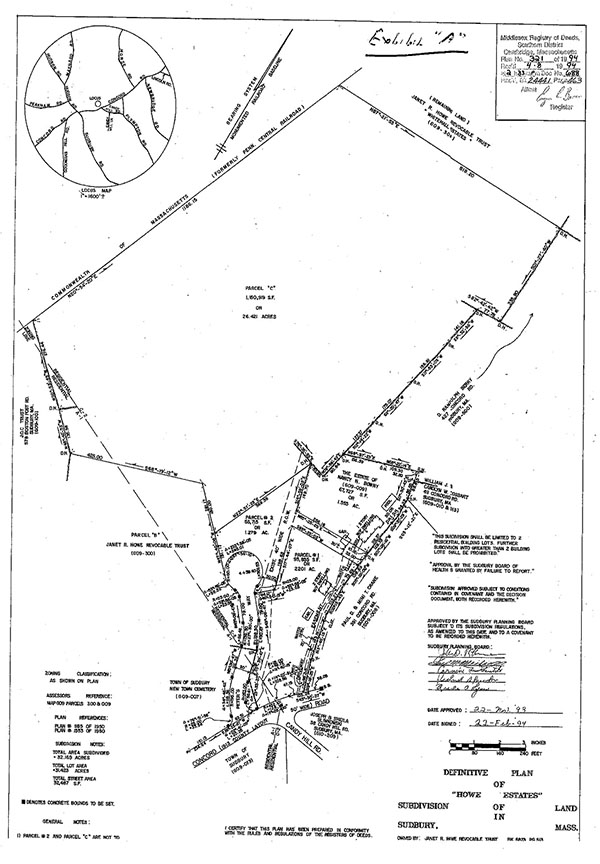

1. By a definitive subdivision plan recorded in the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds (the "Registry") on April 8, 1994, as Plan 321 of 1994, the trustees of the Janet R. Howe Revocable Trust subdivided property abutting the northern boundary of Concord Road into four parcels (the "Subdivision Plan"). This Plan was approved by the Sudbury Planning Board on November 22, 1993, and signed on February 22, 1994. See attached Appendix A.

2. As depicted on the Subdivision Plan, Peter's Way is a fifty-foot-wide street that extends northwesterly from Concord Road. It terminates in a cul-de-sac that is 120 feet in diameter. It remains a paper street.

3. Parcel 1 is a 2.2 acre parcel to the east of Peter's Way. The southern half of Parcel 1's western boundary abuts Peter's Way, and the northern half of Parcel 1's western boundary abuts Parcel 2.

4. Parcel 2 is a 1.28 acre parcel north of Peter's Way and west of Parcel 1. Its southwestern boundary intersects with Peter's Way approximately halfway up the western curve of the cul-de-sac; its eastern boundary runs past the eastern curve of the cul-de-sac, and then turns westerly in towards Peter's Way, intersecting the Way just before the eastern curve of the cul-de-sac begins. Parcel 2 thus abuts the entire circumference of the cul-de-sac other than its southwestern arc. It does not abut the preceding portion of Peters Way that leads to the cul-de-sac.

5. The parcel entitled the Estate of Nancy Bowry (the "Estate Parcel") is a 1.56 acre parcel north of Parcel 1, and east of Parcel 2. It does not abut Peter's Way.

6. Parcel C is a 26.42 acre parcel to the north of Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel. It does not abut Peter's Way.

7. The Subdivision Plan also depicts a 40-foot Right of Way that begins on Parcel 1, running along Parcel 1's western boundary and abutting Peter's Way; the right of way then continues onto Parcel 2, abutting the eastern edge of that parcel and traveling northward until terminating just beyond the lot line of Parcel C and Parcel 2. This right of way provides access to Concord Road for Parcel C.

8. Also shown on the Subdivision Plan, but not included as part of the subdivision, are Parcel B, also owned by the subdivider, the Trustees of the Janet R. Howe Revocable Trust, and a parcel owned by the Town of Sudbury and identified as the New Town Cemetery. Parcel B and the Town parcel are shown on the Subdivision Plan as abutting Peter's Way on the western side of the roadway from Concord Road to the base of the cul-de-sac.

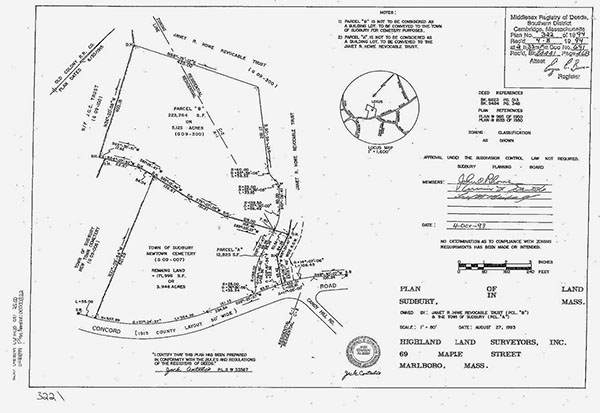

9. Parcel B was created as a result of the approval on October 4, 1993 by the Sudbury Planning Board of a G.L. c. 41, § 81P "approval not required" plan ("ANR Plan"), which also facilitated the creation of Peter's Way by setting aside a parcel ("Parcel A") for eventual inclusion in Peter's Way. The ANR Plan was recorded at the Registry on April 8, 1994 as Plan No. 322 of 1994. See attached Appendix B.

10. By a deed dated April 7, 1994, and recorded at the Registry in Book 24441, Page 473, the Trustees of the Janet R. Howe Revocable Trust conveyed Parcel B to the Town of Sudbury.

11. By a deed dated April 8, 1994, and recorded at the Registry in Book 24441, Page 466, the Trustees of the Janet R. Howe Revocable Trust conveyed Parcel 1, Parcel 2, and Peter's Way to A. Grant Bowry, Jr. and Peter H. Bowry.

12. By a deed dated June 16, 1995, and recorded at the Registry in Book 25416, page 232, A. Grant Bowry, Jr. and Peter H. Bowry conveyed Parcel 1 to Edmund and Jacqueline Skulte, and explicitly reserved to themselves the fee in Peter's Way, stating that "[t]he Grantors hereby reserve for themselves and their successors in title of record the fee in Peter's Way as shown on said plan."

13. By a deed dated October 26, 1995, and recorded at the Registry in Book 25762, Page 518 (the "Bowry Deed"), A. Grant Bowry, Jr. and Peter H. Bowry conveyed Parcel 2, the Estate Parcel, and Peter's Way to the Trustees of the CAS Trust.

14. By a deed dated January 2, 1996, and recorded at the Registry in Book 26857, Page 583 (the "CAS Trust Deed"), the Trustees of CAS Trust conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to Michael Hoffman and Ruby Hoffman.

15. The CAS Trust Deed included the following language: "Meaning and intending to convey and hereby conveying a portion of the premises conveyed by Deed of A. Grant Bowry, Jr. and Peter H. Bowry, to us, dated September 29, 1995, and recorded with said deeds in Book 25762, Page 518." The CAS Trust Deed did not contain any express reference to Peter's Way.

16. After this conveyance, the Trustees of CAS Trust owned no property abutting Peter's Way.

17. On December 27, 2005, the Trustees of CAS Trust executed and delivered a deed, recorded at the Registry in Book 46941, Page 450, conveying Parcel C and purporting to convey Peter's Way to Laura B. Abrams, Trustee of JRH Trust.

18. By a deed dated April 15, 1998, and recorded at the Registry in Book 28454, Page 454, Michael Hoffman and Ruby Hoffman conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to Lida Armstrong.

19. By a deed dated October 26, 1999, and recorded at the Registry in Book 28454, Page 454, Lida Armstrong conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to Lida L. Armstrong as Trustee of the Lida L. Armstrong Revocable Trust.

20. By a deed dated July 18, 2006, and recorded at the Registry in Book 28454, Page 454, Lida Armstrong, Trustee of the Lida L. Armstrong Revocable Trust, conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to Lida L. Armstrong and James Patrick Kelly as Trustees of the Sunflower Revocable Trust.

21. By a deed dated June 29, 2015, Lida L. Armstrong and James Patrick Kelly as Trustees of the Sunflower Revocable Trust conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to plaintiff Erica Andrews.

22. The defendant Sudbury Station LLC applied for a comprehensive permit for the construction of the Project, an affordable housing development on a number of lots to the southwest of Parcel C, owned by defendants JOL Trust, JRH Trust, 24 Hudson Road Trust, Matthew Gilmartin, and Molly Gilmartin. [Note 2] To access the development property, they intend to use Peter's Way as extended by land identified as "Peter's Way Extension" on a plan recorded in the Registry as Plan 907 of 2012; the land comprising this extension, a portion of Parcel B, was deeded to defendant Trustees of JOC Trust by the Town of Sudbury by a deed dated November 7, 2012 and recorded at the Registry in Book 60688, Page 158.

DISCUSSION

The defendants filed a motion to dismiss Count Two pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6), Mass. R. Civ. P., or in the alternative, for summary judgment under Rule 56, arguing that defendant Laura B. Abrams, Trustee of JRH Trust, owns the fee to Peter's Way and that plaintiff Erica Andrews does not own the fee or any other rights in Peter's Way.

The plaintiffs filed an opposition to the motion to dismiss, and a cross-motion for relief under Rule 56(f), Mass. R. Civ. P., requesting that the court decline to rule on the motion as one for summary judgment, as the plaintiffs intend to conduct additional discovery to develop facts necessary to the argument that, in the event that she does not own the fee, Andrews holds an easement in Peter's Way; the plaintiffs also state that they intend to conduct discovery for the purpose of further arguing, in the event that she does in fact own the fee, that none of the defendants have an easement in the way. These are indeed factual issues that may require further development in order to fully dispose of plaintiff's broad request for declaratory judgment as to the defendants' ability to use Peter's Way to access the proposed Project. However, to even reach these questions requires adjudication of the threshold issue whether Andrews does or does not own the fee in Peter's Way. This is a legal issue on which no further factual development is required, and the court therefore need not delay a determination pending any anticipated discovery. As the parties here have introduced evidence outside the pleadings, it is likewise

appropriate to treat the defendants' motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) as one for summary judgment under Rule 56(c). See Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(b).

"Summary judgment is granted where there are no issues of genuine material fact, and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 643-44 (2002); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). "The moving party bears the burden of affirmatively showing that there is no triable issue of fact." Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, supra, 436 Mass. at 644. In determining whether genuine issues of fact exist, the court must draw all inferences from the underlying facts in the light most favorable to the party opposing the motion. See Attorney Gen. v. Bailey, 386 Mass. 367 , 371 (1982), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 970 (1982). Whether a fact is material or not is determined by the substantive law, and "an adverse party may not manufacture disputes by conclusory factual assertions." See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986); Ng. Bros. Constr., Inc. v. Cranney, supra, 436 Mass. at 648. When appropriate, summary judgment may be entered against the moving party and may be limited to certain issues. Community Nat'l Bank v. Dawes, 369 Mass. 550 , 553 (1976); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c).

The issue presented before the court is whether plaintiff Erica Andrews does or does not own the fee in Peter's Way by operation of the derelict fee statute. As the court holds that Andrews owns the fee in Peter's Way, and accordingly enters partial summary judgment in her favor, it is unnecessary to address the plaintiffs' alternative argument that she acquired easement rights. However, Count Two of the Amended Complaint seeks a declaration not only that Andrews holds the fee in the way, but also that the defendants have no right to access the Project site via Peter's Way. As this latter question potentially implicates further questions beyond simply the fee ownership in the way, judgment on Count Two as a whole is withheld, to allow development of the necessary factual question, with respect to the defendants' potential easement rights in the way, and, if appropriate, consideration of a further summary judgment motion on that issue.

The Derelict Fee Statute

G.L. c. 183, § 58, known as the "derelict fee" statute, codified the common law precept that the conveyance of a parcel abutting a roadway is presumed to pass title to the center line of the way if the grantor retained property on the other side of the way, or across the entire width of the way if the grantor did not retain land on the other side. See McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 694 (2010). Under the common law rule, this presumption could be overcome by clear proof of a contrary intent of the parties. Id. This rule was intended "to meet a situation where a grantor has conveyed away all of his land abutting a way or stream, but has unknowingly failed to convey any interest he may have in land under the way or stream, thus apparently retaining his ownership of a strip of the way." See Rowley v. Mass. Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 803 (2003). "The rationale of such decisions is apparently that the grantor is unlikely to want to reserve title to the fee of the way; if he does, he may avoid the effect of the presumption by contraindicating." Smith v. Hadad, 366 Mass. 106 , 108 (1974). In 1971, the common law rule was codified by the adoption of G.L. c. 183, § 58, which provides:

Every instrument passing title to real estate abutting a way, whether public or private, watercourse, wall, fence or other similar linear monument, shall be construed to include any fee interest of the grantor in such way, watercourse or monument, unless (a) the grantor retains other real estate abutting such way, watercourse or monument, in which case, (i) if the retained real estate is on the same side, the division line between the land granted and the land retained shall be continued into such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (ii) if the retained real estate is on the other side of such way, watercourse or monument between the division lines extended, the title conveyed shall be to the center line of such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or

(b) the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding by a side line.

The effect of the statute was "to strengthen 'the common law

presumption that "a deed bounding on a way conveys the title to the centre of the way if the grantor owns to far. " '" Hanson v. Cadwell Crossing, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 497 , 499-500 (2006), quoting Rowley v. Mass. Elec. Co., supra, 438 Mass. at 804, and Gould v. Wagner, 196 Mass. 270 , 275 (1907). "In contrast to the common law, the presumption [of § 58] applies unless the instrument of conveyance 'evidences a different intent [of the grantor] by an express [exception or] reservation,' and extrinsic evidence may not be used to prove the grantor's intent to retain the fee to the way. Nor may that intent be proved, as it could under the common law, by language that the property is bounded 'by a side line' of a way." Rowley v. Mass. Elec. Co., supra, 438 Mass. at 804.

The defendants contend that Andrews cannot claim the benefit of title derived from the rule of construction of Section 58 because Parcel 2 is at the end of Peters Way, and is thus not "abutting a way" for the purposes of the statute; they also alternatively argue that even if Parcel 2 "abuts" Peter's Way for the purposes of Section 58, the fee in Peter's Way was nonetheless expressly reserved pursuant to subpart (b) of the statute and thus is presently owned by defendant Laura B. Abrams, Trustee of JRH Trust. The subpart (b) exception to the statute's presumption of conveyance of the fee in the way, if properly invoked by express reservation of the fee in the deed of conveyance, would have kept the fee from passing to Andrews' predecessors in title, the Hoffmans, and the fee would instead have remained in CAS Trust until later conveyed in 2005 to Laura B. Abrams.

The plaintiffs counter first that Parcel 2 is not at the "end" of Peter's Way, but rather "abuts" Peter's Way for the purposes of the statute. Therefore, they argue, the conveyance of Parcel 2 to Andrews' predecessor in title conveyed all of the grantors' remaining fee in Peter's Way, as it is undisputed that CAS Trust retained no other land abutting Peter's Way after conveying Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to the Hoffmans. The plaintiffs further argue that CAS Trust did not avoid this result because it failed to expressly reserve the fee in Peter's Way when conveying Parcel 2 to the Hoffmans. Therefore, by operation of the statute's rule of construction, that conveyance also passed to the Hoffmans any fee interest that CAS Trust owned in Peter's Way, and because CAS Trust owned the entire fee in Peter's Way, the Hoffmans accordingly acquired the entire fee in Peter's Way. Subsequent conveyances resulted in plaintiff Erica Andrews owning the fee in Peter's Way in conjunction with her ownership of Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel. These arguments are addressed below.

Parcel 2 Abuts Peters Way For Purposes of the Statute.

The parties' arguments present the threshold question whether Parcel 2 is "real estate abutting a way" for the purposes of G.L. c. 183, § 58. The defendants argue that Parcel 2 does not so qualify, and premise this argument on the rule originally articulated in Emery v. Crowley that a parcel at the very end of a way does not abut that way for the purposes of Section 58, and does not, therefore, receive the benefit of the statute's presumption of conveyance. See Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. 489 , 494 (1976). The court in Emery noted that the statute referred only to parcels on one side of the way or the other, without providing for the rights of a parcel at the end; the court further observed that "logically the landowner at the end of a way cannot acquire any fee interest in the way without encroaching on the property rights, if any, of the abutting side owners." Id. In light of this observation, the court concluded that "[t]he term 'abutting,' in the context of fee ownership of ways after conveyance of property bounded on a way, thus refers to property with frontage along the length of a way." Id. See also Diodati v. Kohl, 24 LCR 183 (Mass. Land Ct. 2016) (Speicher, J.), and Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 622-623 (1990) ("Real estate located at the end of a way does not abut the way for the purposes of [G.L. c. 183, § 58] and therefore carries no fee ownership of the way.").

This rule has not yet been applied in the particular circumstances of a parcel situated along the circumference of a cul-de-sac. The status of such a parcel was discussed in dicta by the court in Murphy v. Blalock, but the court did not base its decision on the status under the statute of land along a cul-de-sac. See Murphy v. Blalock, 12 LCR 36 , 41 n.14 (Mass. Land Ct. 2004) (Lombardi, J.). The defendants' argument that parcels along a cul-de-sac are at the end of the way, not along its length, and thus do not abut the way for purposes of Section 58, overstates the breadth of the holding of Emery and misconstrues the reasoning of the Emery court. The reasoning underpinning the holding in Emery suggests a contrary result when a way terminates not in a dead-end but in a cul-de-sac instead.

The court in Emery first noted that the statute referenced parcels only on the sides of the way, and thus concluded that an abutting parcel for the purposes of Section 58 is one which has "frontage along the length of the way." See Emery v. Crowley, supra, 371 Mass. at 494 (emphasis added). Applying this definition to the factual situation of Emery, where the end of a road is simply an edge perpendicular to the sides of the road, a parcel on that edge cannot be considered along the "length" of the road: that final edge provides no additional length, and is an immediate termination of, rather than extension of, its sides. The boundary at the end of the road is perpendicular to the length of the way, not along it. The cases cited by the defendants applying the rule set forth in Emery all concern dead-ends of this nature. The nature of the way's terminus in the case at bar, however, differs significantly. A cul-de-sac does indeed further extend the length of the way. It is composed of sides that carry forward the way in the same direction and along the same course as before, only with the additional feature of curvature, providing additional frontage to the lots along the cul-de-sac. By providing additional frontage, the sides of a cul-de-sac serve to lengthen the way no differently than do the parallel bounds of any other section along the length of a roadway. Indeed, the measurement of the actual length of a road ending in a cul-de-sac is typically to either the center of the circle or its furthest arc, rather than its beginning, thus recognizing the additional length provided by the sides of the cul-de-sac. See, e.g., Woodhouse v. Marot, 16 LCR 76 , 77 (Mass. Land Ct. 2008) (Trombly, J.); Wall St. Dev. Corp. v. Moore, 15 LCR 208 , 212 (Mass. Land Ct. 2007) (Sands, J.), modified sub. nom. Wall St. Dev. Corp. v. Planning Bd., 72 Mass. App. Ct. 844 (2008); Lakeside Bldrs., Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Franklin, 8 LCR 249 , 252 (Mass. Land Ct. 2000) (Green, J.), aff'd 56 Mass. App. Ct. 842 (2002) (measuring to "center line of the turnaround"). It is thus consistent with the rule set forth in Emery to hold that parcels along the circumference of a cul-de-sac abut the way, as a cul-de- sac logically provides frontage "along the length of the way." See id.

Furthermore, application of Section 58 here presents no danger of the unworkably overlapping fees warned of in Emery. In Emery, those parcels situated along the way's sides would take a fee that abuts the final edge of the end of the road, leaving nothing for the end parcel to take in turn; therefore, the grant of the fee to the landowner at the end of the way would necessarily "encroach[] on the property rights, if any, of the abutting side owners." Emery v. Crowley, supra, 371 Mass. at 494. Here, in contrast, while the abutters preceding the cul-de-sac would still obtain the fee in their same sections of the preceding way, these sections would not encompass the cul-de-sac itself. [Note 3] In extending towards the center of the way, the lot lines of parcels with frontage along the cul-de-sac may then extend towards the circle's center point, and this would cause no interference with the rights of the parcels along the portion of the way leading up to the cul-de-sac. [Note 4]

Finally, the overarching purpose of Section 58 would be frustrated if the lots abutting a cul-de-sac were denied the benefit of the statute's rule of construction. Section 58 serves "to meet a situation where a grantor has conveyed away all of his land abutting a way or stream, but has unknowingly failed to convey any interest he may have in land under the way or stream, thus apparently retaining his ownership of a strip of the way or stream." Rowley v. Mass. Elec. Co., supra, 438 Mass. at 803. A grantor in such a situation otherwise would be left inadvertently with "a strip of land, not capable of any substantial or beneficial use by him, after having parted with the land by the side of it

and the ownership of which by him might greatly embarrass the use or disposal, by his grantee, of the lot granted." Boston v. Richardson, 95 Mass. 146 , 153 (1867). Given this potential result, the statute aims to avoid such inadvertent creation of a derelict parcel by instituting a rule of construction that conclusively places the fee in the grantee unless the grantor expressly communicates a contrary intent in the deed of conveyance. As indicated in Emery, a parcel that abuts only the "stub" end of a way presents no possibility of creating a derelict fee when the statute is first applied to the other parcels along the way. Where a road abruptly terminates in a dead-end that is perpendicular to the sides of the way, granting the fee to the parcels along the parallel sides will fully account for the entire fee in the way, because the extended property lines of those parcels will sit flush with the way's dead-end edge. There will thus be no portion of the way at risk of being inadvertently left in the grantor upon conveyance of the additional end parcel. Yet the addition of a cul-de-sac to what would otherwise be the stub end of a way necessarily creates further area that is indeed in danger of becoming derelict, unless it is presumed to be conveyed along with the parcels abutting the cul-de-sac itself. Even if the parcels along the final stretch of the way leading up to the cul-de-sac take the fee in the way as provided by the statute, extending their boundaries towards the center line of the way, the fee in the cul-de-sac itself would remain unaccounted for. Without application of Section 58's rule of construction to the parcels with frontage along the cul-de-sac itself, the fee in that portion of the way would be left behind in the grantor in the precise manner that the statute aims to avoid.

The Deed to the Hoffmans Did Not Expressly Reserve the Fee in Peter's Way.

As Parcel 2 abuts the cul-de-sac of Peter's Way, the fee in the way passed along with Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel pursuant to the deed from CAS Trust to the Hoffmans, unless "the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation

" G.L. c. 183, § 58. [Note 5] Because the grantor, upon conveying Parcel 2 to the Hoffmans, retained no other land abutting Peter's Way, the conveyance would include the entirety of the grantor's fee in the way, absent an express reservation or exception. The next question is therefore whether such an intent is apparent on the face of the deed.

The common law rule for determining whether the grantor had reserved the fee in a road allowed the intent of the parties concerning the fee to be "ascertained from the words used in the written instrument interpreted in the light of all the attendant facts." Suburban Land Co. v. Billerica, 314 Mass. 184 , 189 (1943). However, in requiring the "instrument passing title" to contain an "express reservation", Section 58 renders the presumption of conveyance more difficult to overcome than under its common law predecessor. See G.L. c. 183, § 58; McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 694 (2010). Under this stricter standard, "[o]ther attendant evidence of the parties' intent is no longer probative." Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 244 (1992). Accordingly, "the express reservation of a fee interest that effectively removes an abutting monument from the operation of § 58 must be contained in the deed itself." Id. "It is a rule in the construction of deeds, that the language, being the language of the grantor, is to be construed most strongly against him." Bernard v. Nantucket Boys' Club, Inc., 391 Mass. 823 , 827 (1984).

The Bowry Deed conveyed Parcel 2, the Estate Parcel, and Peter's Way to the CAS Trust. The subsequent CAS Trust Deed to the Hoffmans conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel. It did not reference Peter's Way explicitly. [Note 6] Plaintiffs argue that without explicit reference to Peter's Way, there can be no express exception, and the statute's rule of construction requires the conclusion that the fee in Peter's Way was conveyed as well. Defendants argue that the deed did in fact except the fee in Peter's Way through the following language: "Meaning and intending to convey and hereby conveying a portion of the premises conveyed by Deed of Grant A. Bowry Jr., and Peter Bowry, to us, dated September 29, 1995, recorded with said deeds in book 25762, Page 518" (emphasis added). Defendants argue that by describing the conveyed land as a "portion" of the Bowry Deed land, the CAS Trust Deed expressly excepted Peter's Way from the conveyance because Peter's Way was the portion of the land of the grantors not expressly mentioned in the deed. When the CAS Trust Deed expressly conveyed Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel, Peter's Way was the only remaining unmentioned Bowry Deed land. Defendants argue that this implicit reference to the remaining land as another "portion" of the grantors' land must, then, have been intended as a reservation of Peter's Way. Since the road is the only remaining Bowry Deed parcel not mentioned in the conveyance, the only way for the conveyance to actually constitute a "portion" of the Bowry Deed land is for the fee in the way to remain in the grantor. Otherwise, the defendants argue, the conveyance would consist of all of the Bowry Deed land. Thus, the defendants rather elliptically argue that the CAS Trust Deed expressly reserved the fee in Peter's Way by leaving it as the only parcel owned by the trust that was not expressly mentioned in the deed. This is exactly the opposite of what the statute requires in order to successfully exclude the fee in a way from a conveyance of land abutting the way.

As the plaintiffs argue, one must look outside the four corners of the CAS Trust deed itself in order to make the inference suggested by the defendants. For one to ascertain that the only other land in the Bowry Deed is Peter's Way, and thus make the conceptual leap that Peter's Way is not intended to be conveyed, one must examine the Bowry Deed. The plaintiffs thus contend the need to look beyond the four corners of the CAS Deed necessarily prevents the claimed reservation from being the "express exception or reservation" required by the statute. They rely on the court's holding in Tattan v. Kurlen that "the express reservation of a fee interest that effectively removes an abutting monument from the operation of § 58 must be contained in the deed itself, not some other document." Tattan v. Kurlen, supra, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 244.

The holding in Tattan is perhaps not quite as broad as argued by the plaintiffs, since it involved a reference to a plan, and not to a deed, but the principle of the holding is nevertheless apt and instructive in the present case. In Tattan, the deed referenced a plan that depicted a parcel labeled as "reserved for future street purposes." Id. at 242. The court reasoned that the rule allowing the incorporation of plans in particular "was not intended and has never been used to determine title -- i.e., the quality and durational extent of the estate taken by the purchaser." Tattan v. Kurlan, supra, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 246-247. The court also noted that "[t]he plain language of the statute speaks only of 'instrument[s] passing title,' that is, deeds", not plans. Id. at 247. It is certainly possible that the court thus intended its holding to be limited to reservations dependent on reference to plans, while not foreclosing those relying on reference to other deeds. This conclusion gains further plausibility when viewed in light of the typical rule that cross- referencing another deed has "the same effect as if the entire description in that deed had been copied into each conveyance." Abbott v. Frazier, 240 Mass. 586 , 593 (1922).

However, while Tattan may not provide the concrete prohibition suggested by plaintiffs against examining other deeds incorporated by reference, the language of even the combined deeds fails to meet the standard required by the statute and by Tattan. The principle underlying the requirement for an express reservation is that there is "clear proof of a contrary intent." See Silva v. Planning Bd. of Somerset, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 339 , 343 (1993). Even considering the defendants' proposed interpretation and allowing reference to the earlier deed, the language of the CAS Trust Deed fails to satisfy this requirement, as it is built upon implication and inference rather than any clear, express declaration. The defendants essentially argue that by expressly referring to the land actually conveyed to grantees as a particular portion of the premises previously received by them, the grantors must have intended to also reserve for themselves the remaining, unmentioned portion of their land. If this is to be characterized as a reservation, it is unavoidably implicit and inferential rather than express. That the extent of the claimed remainder can perhaps be determined with some certainty by examining prior deeds does not change the fact that only the land being conveyed, and not the land being reserved, is ever directly described in the deed of conveyance, and the grantor's fee in the unmentioned remainder can only be deduced by inference. Nor is the inference straightforward or plainly apparent, as it requires one to examine the full extent of the prior deed's grant, compare it to its successor, determine that Peter's Way is the difference in the express grant, note the reference in the latter grant as a portion of the prior, and finally from this disparate information infer that the latter deed's description of the conveyed land as "a portion" of the former must be intended to exclude Peter's Way. The very need to ascertain the grantor's undescribed fee in an unmentioned monument by inference, particularly an inference requiring such comparison of provisions and deeds, runs directly contrary to the nature of an "express" reservation, and may by no means serve as the "clear proof of a contrary intent" traditionally required to overcome the presumption embodied in Section 58. See Silva v. Planning Bd. of Somerset, supra, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 343.

Indeed, a comparison of the June, 1995 Bowry Deed of Parcel 1; the September, 1995 deed of Parcel 2, the Estate Parcel and Peter's Way to the Trustees of CAS Trust; and the January, 1996 CAS Trust Deed that failed to mention Peter's Way, demonstrates a likely awareness by the Trustees of CAS Trust that they were not expressly reserving the fee to Peter's Way in the CAS Trust Deed to the Hoffmans. All three deeds, executed and delivered in a span of less than eight months, were notarized by the same notary public and attorney, and the latter two deeds, as is to be expected in successive deeds of related parcels, contained language that was taken verbatim from the earlier deeds. However, the June, 1995 deed of Parcel 1 contained the following express reservation, which is nowhere to be found in the CAS Trust Deed of Parcel 2, delivered less than eight months later: "The Grantors hereby reserve for themselves and their successors in title of record the fee in Peter's Way as shown on said plan." This presence of such an explicit and express reservation in a deed so recent in the chain of title is further evidence that no such reservation was intended when Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel were deeded out several months later without the presence of such an explicit and express reservation.

This claimed reservation in the CAS Trust Deed is similar to claims of implicit reservation previously rejected by this and other courts. In Holy Spirit Ass'n for the Unification of World Christianity v. Posten, the deed contained a clause granting "the right to use [the way] in common with the grantor and all other persons entitled thereto." Holy Spirit Ass'n for the Unification of World Christianity v. Posten, 18 LCR 169 , 172 (Mass. Land Ct. 2010) (Grossman, J.), aff'd No. 10-P-789, Mass. App. Ct. (Aug. 8, 2011). The plaintiffs in that case argued that it would be superfluous to include such a grant of use rights, if the entire fee (and thus all accompanying rights) in the way were instead intended to pass to the grantees; thus they contended that by including this limited grant of rights, they expressly reserved the underlying fee. The Land Court rejected this notion, finding that the language was not sufficiently clear evidence of such an intent. See id. The Appeals Court rejected a similar claimed reservation in Tattan, where it found no express reservation of the underlying fee despite the fact that a deed conveyed to the grantee "the right, in common with others, to pass and repass" over a way. [Note 7] See Tattan v. Kurlan, supra, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 241.

The argument asserted by the grantors in Holy Spirit, and implicit in the comparable language of the deed in Tattan, is that the only reason for the grantor to expressly grant a limited right in the way is because it had retained the underlying fee; this requires an inference that by expressly granting only limited rights, the grantor intends to retain the remainder, even if that intent is not explicitly stated. This was rejected in both cases as an insufficiently express reservation. Here, similarly, the defendants argue that by expressly stating an intention to convey just a portion of the land, it should be inferred that they intended to retain the remainder. In both situations, the reservation is not explicitly stated, but instead is at best implicit. This is not "express" for the purposes of Section 58. This can be contrasted to the express reservation found by this court in Del Torchio v. Movali, where the deed not only conveyed an easement in a disputed way to the grantee, but also described the way itself as a "proposed road, forty (40) feet wide over remaining land of grantor." See Del Torchio v. Movali, 17 LCR 137 , 141 (Mass. Land Ct. 2009) (Grossman, J.) (emphasis added). The court found this language to be "clear evidence of contrary intent

in the source deed," as this phrase made it "obviously intended and understood that this land [burdened by the right of way] was retained by the grantor." Id., quoting Emery v. Crowley, supra, 371 Mass. at 493. That language made an explicit statement describing the grantor's, rather than grantee's, fee, and there was no need to resort to inference to determine those rights. See id.

Moreover, the obscure nature of the reservation asserted by the defendants is accentuated by contrast to other reservations contained within the deed itself that are undoubtedly express. The CAS Trust Deed contains a provision stating: "The Grantors reserve for themselves and their successors in title of record to other land of CAS Trust, which presently abuts said 40 foot Right of Way and Parcel No. 2, [Note 8] a Right of Way over the existing 40 foot Right of Way shown on said Plan together with a Right of Way over the remainder of Parcel #2 lying westerly thereof

The Grantors further reserve for themselves and their successors in title to other land of CAS Trust

the right to repurchase from the Grantees or the Grantees' successors in title of record the fee to both rights of way described herein

" These reservations are abundantly clear and direct, and undoubtedly qualify as express. Their inclusion further demonstrates that the grantors certainly possessed the ability to implement language expressly excepting or reserving a particular right, and they did so twice. They could have utilized similar language for a third time to expressly reserve the fee in Peter's Way. They chose not to do so. It may be presumed that, had the grantors intended to reserve the right in the way, they would have again employed this same or similar express language that is indeed typical and customary in conveyancing practice, and which was used in the deed of Parcel 1 less than eight months earlier.

Accordingly, the court concludes that the deed from CAS Trust to the Hoffmans did not expressly reserve the fee in Peter's Way. By operation of G.L. c. 183, § 58, whatever fee in Peter's Way CAS Trust owned thus passed to the Hoffmans. CAS Trust had acquired the fee in all of Peter's Way through the conveyance of the Bowry Deed. When CAS Trust conveyed Parcel 1 to the Skultes prior to its conveyance of Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel to the Hoffmans, it expressly reserved the fee in the way. As of the time of the deed to the Hoffmans, CAS Trust thus owned the entire fee in the way, and this fee then passed to the Hoffmans along with Parcel 2 and the Estate Parcel. In the subsequent deeds from the Hoffmans to Lida Armstrong, from Armstrong to the Lida L. Armstrong Revocable Trust, from that Trust to the Sunflower Trust, and from the Sunflower Trust to plaintiff Erica Andrews, there are no reservations of the fee in Peter's Way. The fee in the way thus passed by each of those conveyances, and ultimately came within the possession of Andrews.

As Andrews holds the fee in Peter's Way, it is unnecessary to address the alternative argument that Andrews acquired an easement by estoppel. The plaintiffs are entitled to summary judgment on the limited issue of the fee in the way; their claim for declaratory judgment, however, is broader than this issue alone, as they seek a declaration that the defendants have no legal right at all to use the way for their proposed Project. [Note 9] The plaintiffs accordingly have requested the opportunity to further submit a motion for summary judgment on the issue of the defendants' potential easement rights in Peter's Way. Thus, while the plaintiffs are entitled to partial summary judgment, this will not dispose of Count Two in its entirety. The question whether and to what extent any of the defendants have title rights over Peter's Way other than the fee, remains an open issue.

Modification Under the Subdivision Control Law, G.L. c. 41, § 81W.

Plaintiffs argue that plans of defendant Sudbury Station LLC to use a strip of land identified as the "Peter's Way Extension", which is outside the Peter's Way subdivision itself, as a means of access for their development requires a modification of the subdivision pursuant to

G.L. c. 41, § 81W. This argument is unrelated to Count Two, which concerns only the rights to use the way designated on the Subdivision Plan as Peter's Way. As it is essentially an argument that the Board, or the Planning Board, failed to grant a necessary approval for the affordable housing development, it pertains solely to Count One, which has been stayed, and thus will not be addressed by the court while the stay is in place.

CONCLUSION

Peter's Way ends in a cul-de-sac, and parcels with frontage along this cul-de-sac are entitled to the benefit of G.L. c. 183, § 58's rule of construction. CAS Trust owned the entire fee in Peter's Way when it conveyed Parcel 2, and did not in that conveyance expressly reserve the fee in Peter's Way; through operation of G.L. c. 183, § 58, the fee in Peter's Way thus passed to the Hoffmans. None of the subsequent transfers of Parcel 2 expressly reserved the fee in the way, which then passed with each conveyance. Plaintiff Erica Andrews therefore currently owns the fee in Peter's Way. A final declaration on Count Two, however, cannot be entered as a result of this conclusion, as further proceedings are necessary to fully adjudicate the plaintiffs' request for a declaration with respect to other legal rights the defendants may or may not have to use Peter's Way to access the Project site.

The court will schedule a telephone conference with the parties to determine further proceedings necessary relative to the resolution of all issues pertaining to Count Two of the Amended Complaint.

So Ordered.

KEVIN L. TIGHE, TRUSTEE of the HUDSON ROAD TRUST NO. 1, ERICA ANDREWS, NICHOLAS A. TRITOS, ROANNA M. LONDON, SCOTT O'NEIL, WILLIAM N. CARLOUGH, III, ELEANOR G. CARLOUGH, ROBERT LEE, and RAYMOND D. LIBERATORE and CLAUDIA L. LIBERATORE, as TRUSTEE of the 41 CODMAN DRIVE REALTY TRUST v. JONATHAN F.X. O'BRIEN, NICHOLAS B. PALNER, JEFFREY P. KLOFFT, JONATHAN G. GOSSELS, and NANCY G. RUBENSTEIN, as they comprise the SUDBURY ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, SUDBURY STATION LLC, MATTHEW S. GILMARTIN, MOLLY F. GILMARTIN, and LAURA B. ABRAMS.

KEVIN L. TIGHE, TRUSTEE of the HUDSON ROAD TRUST NO. 1, ERICA ANDREWS, NICHOLAS A. TRITOS, ROANNA M. LONDON, SCOTT O'NEIL, WILLIAM N. CARLOUGH, III, ELEANOR G. CARLOUGH, ROBERT LEE, and RAYMOND D. LIBERATORE and CLAUDIA L. LIBERATORE, as TRUSTEE of the 41 CODMAN DRIVE REALTY TRUST v. JONATHAN F.X. O'BRIEN, NICHOLAS B. PALNER, JEFFREY P. KLOFFT, JONATHAN G. GOSSELS, and NANCY G. RUBENSTEIN, as they comprise the SUDBURY ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, SUDBURY STATION LLC, MATTHEW S. GILMARTIN, MOLLY F. GILMARTIN, and LAURA B. ABRAMS.